A new study shows that exposure to the color cyan (a shade of bright blue-green) via television or computer screens could greatly impact one’s sleep.

The research was conducted by Professor Robert Lucas and Dr. Annette Allen of the University of Manchester, who together developed a special TV that could either infuse or remove cyan from an image without affecting its color quality. Essentially, they figured out how to produce the color cyan without actually using any cyan in the image, which they hoped would allow them to study the color’s effects on slumber.

“The easiest way to explain this idea is by comparing it to mixing paints,” Prof. Lucas told me over the phone. “To get the color green, most people know that you mix together blue and yellow. But you can also combine yellow and cyan and get the same green. Therefore, it’s not the color cyan itself that brings about restlessness in the human brain, but the wavelengths produced by it.”

And what exactly is it that these wavelengths trigger? According to Lucas, cyan engages a particularly light-sensitive photoreceptor in the eye called melanopsin, which, when excited, can prevent someone from falling asleep.

To better understand melanopsin’s role in wakefulness, Prof. Lucas and Dr. Allen had their study participants watch a movie on the aforementioned TV screen with our without primary cyan. Afterward, the participants were asked to rate how sleepy they felt and provide the researchers with a saliva sample, which they would then measure for levels of the sleep hormone melatonin.

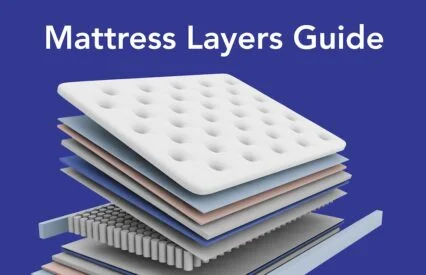

Looking for a new bed? Check out our full Casper Mattress Review!

What the scientists found was that participants felt more alert when watching a movie with cyan and sleepier when the cyan was removed. The melatonin levels also backed this up, showing heavier amounts of the hormone in the latter group.

“From a scientific perspective, the most interesting thing this tells us is that melanopsin is really important in determining whether or not someone’s tired,” explained Lucas. “So, figuring out how to manipulate this photoreceptor cold be helpful for improving sleep hygiene.”

FIGURING OUT NEXT STEPS

While Lucas and his team admit the findings are exciting, he added that this is just the beginning. In truth, the results only indicate the likelihood of someone feeling ready for sleep and don’t yet demonstrate whether or not someone would actually sleep better with limited cyan exposure.

“We certainly are continuing to work with this device and with these ideas,” he concluded. “A big question for us moving forward: Does what we see here at the onset translate to how participants sleep afterward? We’ve measured whether they want to go to sleep, not necessarily the quality of the sleep, so that’s what we hope to address in the future.”

For more on the latest in sleep science, check out our coverage of studies looking at the benefits of yoga and the daily impact of caffeine.