The mystery of dreams has captivated people for millennia. And while life in the 21st century (and the unprecedented access to information that comes with it) leaves us with relatively few mysteries, some questions remain. Take sleep and dreams, for example. With all we know about sleep, questions about the purpose and nature of dreams still remain. What are dreams? Are they messages from the subconscious? An expression of repressed desires, as Sigmund Freud proffered? Or are they meaningless and completely random firing of neurons in the brain?

Suffice it to say dreams are a complex topic — here’s what we know.

Long Story Short

- Dreams are involuntary mental images or sensory experiences that occur during sleep.

- Dreaming is not unique to REM sleep. Dreams in non-REM stages occur; however, they’re often less vivid and poorly recalled.

- Dream recall isn’t as easy as it sounds, but keeping notes and journaling may help you remember your dreams.

What Are Dreams?

Dreams are a series of involuntary thoughts, visual images, and emotional responses that occur during sleep. Sounds and physical sensations may also be a part of the experience.

Scientifically, dreams appear to be triggered by a decrease in the slow-wave activity (SWA) of posterior brain regions. Once thought to only occur only during the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep, newer research has shown that dreams can occur in any sleep stage, although they tend to be more vivid during REM sleep (more on that later). If you’re wondering how your dream imagery compares to others, the evidence suggests that some people dream in color while others dream in black and white. (1)

And in anticipation of your next question — yes, everyone dreams. Most people spend about two hours each night dreaming, though most may not remember their dreams upon waking. (1)(2) Believe it or not, your personality, creative aptitude, mental health, cognition, and general health can all play a role in your ability to remember your dreams. Research also shows that dream recall may largely depend on when you wake up (during non-REM sleep or REM sleep) and the content of your dream (pleasant imagery versus disturbing imagery). For women, it may be easier to recall dreams during certain phases of their menstrual cycle. (2) (3)

Why Do We Dream?

Daniel Glazer, a clinical psychologist and co-founder of several health technology platforms, including US Therapy Rooms, tells us that while the “why” behind dreaming is still being actively investigated by researchers in the fields of psychology and neuroscience, theories abound. “At the most basic level, dreams happen because our brains are just firing differently during sleep,” he says. (4) “And while some think dreams serve no real cognitive purpose. Others theorize they could aid crucial functions like memory consolidation, emotional processing, or even unconscious problem-solving.” (4)

Carleara Weiss, Ph.D., MSH, RN, and Sleep Science Advisor for Aeroflow Sleep, adds that while some schools of thought suggest that “Dreams can help us navigate unresolved issues, fears, or desires, (5) others believe that dreaming helps the brain clear space and reorganize itself to remain productive.”

For more on the theories behind why we dream, click here.

Dreams in REM Sleep vs. Non-REM Sleep

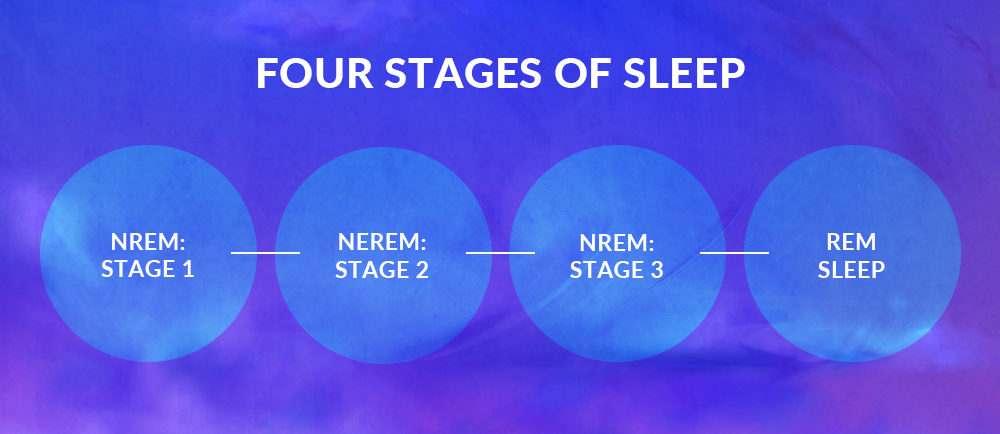

Once thought to occur only during the REM stage of sleep, new evidence suggests that dreams can and do occur during all stages of non-REM sleep. (6) Though dreaming takes place during all four stages of sleep, including the three non-REM phases, the nature of dreams may be quite different depending on the stage during which they occur. (7)

REM dreams tend to be more hallucinatory, vivid, and story-like, and sleepers tend to have higher recall rates, whereas dreams outside of REM sleep are typically not as vivid or memorable. (7)

Despite the vividness of these dreams — and any running, punching, or flying you might have been doing — you may notice that you always wake up safe and sound wherever you fell asleep.That’s the reticular activating system (RAS) at work. The RAS, which typically occurs during REM sleep, keeps us from moving our extremities during our dreams. (8) So when we’re throwing a punch at that 10-foot alien, we’re not inadvertently landing one on our bedmates.

Different Stages of Sleep

Sleep architecture (how our sleep is organized) is broken down into non-REM and REM sleep; non-REM sleep is further broken down into three sleep stages: (4)

- N1. This is the lightest stage of sleep, often described as the transition between the sleep and wake states.

- N2. A slightly deeper phase of sleep where heart rate and body temperature typically drop. Most of the time spent asleep is spent in N2 sleep. (4)

- N3. Also known as slow-wave sleep, deep sleep, and delta sleep, N3 is the deepest and most restorative phase of sleep. This is the growth and repair stage of sleep, which includes the release of human growth hormone, the building of bone and muscle, and the strengthening of the immune system. (4) (9)

- REM. This is the Rapid Eye Movement portion of a sleep cycle where brain activity most closely resembles that of being awake and the stage most closely linked to dreaming. This sleep stage is characterized by muscle atonia (reduced muscle tone that prevents you from acting out your dreams) and erratic breathing and heart rate. (4)

Dreaming in N1 (formerly Stage One)

“Dreams” during N1 (or sleep onset) are more likely to be simple flashes of imagery, which tend to disappear as the sleeper falls deeper into sleep. (7)

Dreaming in N2 (formerly Stage Two)

Like N1 dreams, N2 dreams are more likely to be isolated visual imagery. Moreover, sleepers awakened during N2 are more likely to report no dream content or white dreams — the sleeper feels as though they had a dream but is unable to recall any content. (7)

Dreaming in N3, or Slow Wave Sleep (formerly Stages 3 and 4)

There’s relatively little research demonstrating the nature of dreams and dreaming during slow-wave or deep sleep. What we do know, however, is that this stage is the most difficult to awaken from and also when sleepwalking, night terrors, and bedwetting typically occur. (4)

Dreaming in REM Sleep

Dreaming happens during non-REM sleep, but it seems that REM sleep is where the magic happens. Dreams during the REM stage are usually more of an elaborate narrative, and when sleepers are awakened during REM sleep, recall rates can be as high as 80 percent. (7)

We’ll add here that while recall rates may be high, they’re still fleeting. Anyone who wants to remember their dreams upon waking should consider keeping a pen and paper by their bed to record their dream content.

Additionally, brain activity during REM sleep shows mixed brain waves that closely resemble those seen during the waking state, so it’s possible that REM sleep dreams may be more vivid than those that occur during non-REM sleep due to activation of the brain’s visual cortex. (4)(10)

Different Types of Dreams

Here’s a quick rundown of some of the more common different types of dreams people can have.

Vivid Dreams

Vivid dreams are intensely realistic, easy to remember, and tend to stay with the dreamer once they wake. They feel similar to real memories and are often associated with dream enactment behavior. (11)

Lucid Dreams

Lucid dreams are dreams in which the dreamer becomes aware that they are dreaming. Lucid dreamers often have control over the narrative of their dream, exhibit critical and logical thinking akin to that of an awake mind, and often have full memory of the events in their dream. (12) Lucid dreaming is quite rare, with only half of the population having experienced a lucid dream in their lifetime. (13)

Nightmares

Nightmares are vivid dreams with distressing content and mental imagery. (14) Research indicated that nightmares may be accompanied by physical symptoms of anxiety (e.g., sweating and shortness of breath) and ultimately disrupt and wake the sleeper. The most common themes of nightmares are physical aggression, failure, or helplessness. (14)

Common causes of nightmares include: (15)

- Stress or anxiety

- Sleep deprivation

- Trauma/PTSD

- Medications

- Mental health disorders

- Scary books and movies

What Can I Do About Nightmares?

Considering that nightmares may stem from lifestyle factors, it stands to reason that lifestyle choices and some fine-tuning to your sleep hygiene may help keep them at bay. (15) (16)

To keep nightmares in check:

- Establish a solid (and soothing) bedtime routine

- Skip the alcohol

- Don’t eat right before bed

- Review any medications you’re taking (speak with your doctor or pharmacist if you’re concerned about a link to nightmares)

- Try some stress-relieving activities before bed

- Don’t watch scary movies before bed

Nightmares vs. Night Terrors

Nightmares and night terrors may get mixed up, but they are different experiences. Nightmares are bad or scary dreams that sleepers usually recall the next day. Nightmares can happen to anyone at any age, while night terrors are more common among kids and are characterized by abrupt awakenings, intense screaming, and thrashing. Sleepers are usually hard to wake, and they don’t typically recall the experience. More on that below.

Night Terrors

Night terrors (also known as sleep terrors) are episodes of extreme terror. (17) Most common in children between the ages of 4 and 12 years of age, night terrors are marked by abrupt waking from sleep accompanied by screams of terror and intense fear. Those who suffer from night terrors are typically incoherent, difficult to arouse, and often have no memory of the event. More often than not, the end of a night terror is as abrupt as the start, and the child will fall back into a deep sleep on their own. Most children will outgrow night terrors by late adolescence. (17)

Recurring Dreams

Recurring dreams are dreams that someone experiences repeatedly over time. Recurring dreams tend to feature the same themes, people, and places. According to existing research, somewhere around 50 percent to 75 percent of adults have reported at least one recurring dream in their lives — most of which are negative in nature (i.e., being chased). (18) Right now, there are no black-and-white answers as to what causes recurring dreams; however, experts believe that recurrent dreams are deeply linked to the individual’s emotional well-being and a reflection of what’s going on in your waking life.

How Can Dreams Affect My Sleep?

“Dreams are often a sign of good, healthy sleep,” says Weiss. “They usually don’t impact sleep unless they refer to traumatic experiences or distressful emotions. In that case, dreams can cause fear, increase traumatic feelings, and lead to insomnia.”

Tips for Remembering Dreams

No doubt most of us have woken up from a wonderfully pleasant or extremely bizarre dream, vowing to remember it the next day. But as we’ve already established — dream recall is hard. Ahead, Justina Lasley, founder of the Institute for Dream Studies and author of Wake Up To Your Dreams, shares a few tips for jogging your memory.

- Set Your Intention. “Our brains are not wired to remember our dreams, so intention makes a big difference,” says Lasley.

- Write It Down. According to Lasley, one of the best ways to commit a dream to memory is to write it down.

- Pro tip: Lasley says, “Keep a paper and pencil (or use your phone for notes if you prefer), and when you wake from a dream, take a few minutes to jot down some notes to help you remember.”

- Reflect upon waking. Instead of jumping into your day immediately after waking, Lasley suggests lying quietly in bed for a bit and allowing the dream to come back to you.

- Get Comfy. With a trick she swears by, Lasley suggests rolling over to your most comfortable sleeping position to help with dream recall.

- Write in the Present Tense. According to Lasley, writing in the present tense helps you re-enter the dream and get into the action and emotion — all of which help with recall.

These tips aren’t a guarantee that your dream recall will improve, but if you’re invested, they may be worth a shot!

Keeping a Dream Journal

For those interested in exploring the meaning of their dreams, Lasley suggests keeping a dream journal. When transcribing your notes in the morning, she says to capture the dream as it is and try to refrain from dissecting it while transcribing. The time for making connections and contemplating the dream will come later.

Oneirology: The Study of Dreams

The word oneirology comes from the Greek and means the study of dreams. Oneirology involves the search for correlations between brain function and the act of dreaming, in particular, the connection between dreams, memory, and psychological disorders.

Some common themes explored in oneirology include dreams of:

- Flying – Dreams of flying may indicate a release from limitations or spiritual freedom.

- Losing teeth – Teeth falling may indicate some type of transition.

- Falling – Dreams of falling may indicate a lack of confidence or insecurity with some situation.

We’ll add here that while it’s tempting to look up the meaning of your dream online or in books, their meaning can and will vary from person to person even if some of the elements look the same. Dream symbolism is best explored while considering the goings on in a person’s life and their unique experiences.

How to Interpret Your Dreams

There are no hard and fast rules for interpreting dreams (and research is mixed and still in progress), but here are a few tips for those who are interested.

- Write down the content of your dreams as they occur.

- Keep a dream journal.

- Think about what’s going on in your life at that point in time and your unique experiences.

- Consult a professional or trusted source.

Does everybody dream?

Everyone dreams. Most people spend about two hours each night dreaming, though most may not remember their dreams upon waking. (1)

Can I wake myself up from a dream?

Our research revealed that there’s little scientific proof to support the idea that we can wake ourselves from a dream. Anecdotally, however, there is some evidence to suggest that calling out for help in your dream or blinking may do the trick.

Does melatonin affect dreams?

Some anecdotal evidence suggests that melatonin can affect dreams because it extends overall sleep duration and increases the amount of time spent in REM sleep — the stage where we tend to have longer, more vivid dreams.

Can dreams predict the future?

While it may feel like your dream may have been prophetic, it’s likely just coincidental. There’s no current scientific evidence to suggest dreams can predict the future.

The Last Word From Sleepopolis

Because dreams are so individual and represent the life and concerns of each person who dreams, we may never fully understand their purpose or meaning. Still, recent advances in sleep science and neurology have given us tantalizing glimpses into the nature of dreams and the fascinating brain processes that lead to dreaming.

Sources

- Paris, H. (2020). Subjective dream experiences index students’ waking affect, individual concerns, conflict, and unconscious thoughts. UC Santa Barbara: Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities Journal. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hs3585w

- Dal Sacco D. Dream recall frequency and psychosomatics. Acta Biomed. 2022;93(2):e2022046. Published 2022 May 11. doi:10.23750/abm.v93i2.11218

- Ilias I, Economou NT, Lekkou A, Romigi A, Koukkou E. Dream Recall and Content versus the Menstrual Cycle: A Cross-Sectional Study in Healthy Women. Med Sci (Basel). 2019;7(7):81. Published 2019 Jul 21. doi:10.3390/medsci7070081

- Patel AK, Reddy V, Shumway KR, et al. Physiology, Sleep Stages. [Updated 2024 Jan 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526132/

- Zhang, W., & Guo, B. (2018, August 6). Freud’s Dream Interpretation: A different perspective based on the self-organization theory of dreaming. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01553/full

- Scarpelli, S., Alfonsi, V., Gorgoni, M., & Gennaro, L. D. (2022). What about dreams? State of the art and open questions. Journal of Sleep Research, 31(4), e13609. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13609

- Martin, J. M., Andriano, D. W., Mota, N. B., Mota-Rolim, S. A., Araújo, J. F., Solms, M., & Ribeiro, S. (2020). Structural differences between REM and non-REM dream reports assessed by graph analysis. PLOS ONE, 15(7), e0228903. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228903

- Arguinchona JH, Tadi P. Neuroanatomy, Reticular Activating System. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549835/

- Zaffanello, M., Pietrobelli, A., Cavarzere, P., Guzzo, A., & Antoniazzi, F. (2024). Complex relationship between growth hormone and sleep in children: Insights, discrepancies, and implications. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 1332114. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1332114

- Igawa, M., Atsumi, Y., Takahashi, K., Shiotsuka, S., Hirasawa, H., Yamamoto, R., Maki, A., Yamashita, Y., & Koizumi, H. (2001). Activation of visual cortex in REM sleep measured by 24-channel NIRS imaging. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 55(3), 187-188. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00819.x

- Fattal D, Platti N, Hester S, Wendt L. Vivid dreams are associated with a high percentage of REM sleep: a prospective study in veterans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023;19(9):1661-1668. doi:10.5664/jcsm.10642

- Tan, S., & Fan, J. (2023). A systematic review of new empirical data on lucid dream induction techniques. Journal of Sleep Research, 32(3), e13786. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13786

- Schredl M, Remedios A, Marin-Dragu S, et al. Dream Recall Frequency, Lucid Dream Frequency, and Personality During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Imagin Cogn Pers. 2022;42(2):113-133. doi:10.1177/02762366221104214

- Sheaves, B., Rek, S., & Freeman, D. (2023). Nightmares and psychiatric symptoms: A systematic review of longitudinal, experimental, and clinical trial studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 100, 102241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102241

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2021b, June 5). Nightmare disorder. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/nightmare-disorder/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353520

- (PDF) efficacy of a brief treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances for Veterans. (n.d.-c). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277251541_Efficacy_of_a_Brief_Treatment_for_Nightmares_and_Sleep_Disturbances_for_Veterans

- Leung AKC, Leung AAM, Wong AHC, Hon KL. Sleep Terrors: An Updated Review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2020;16(3):176-182. doi:10.2174/1573396315666191014152136

- Schredl, Michael & Germann, Luca & Rauthmann, John. (2022). Recurrent Dream Themes: Frequency, Emotional Tone, and Associated Factors. Dreaming. 32. 10.1037/drm0000221.

Glazer, Daniel. Personal Interview. May 28, 2024.

Lasley, Justina. Personal Interview. May 29, 2024.

Weiss, Carleara. Personal Interview. May 30, 2024