Sleepwalking — technically known as somnambulism — is a sleep disorder characterized by walking, sitting up in bed, and performing other movements while asleep. Sleepwalking is considered a parasomnia, a sleep disorder that involves abnormal or disruptive movements or behaviors. In addition to sleepwalking, parasomnias include sleep-eating, talking while asleep, sleep paralysis, night terrors, and hypnagogic hallucinations.

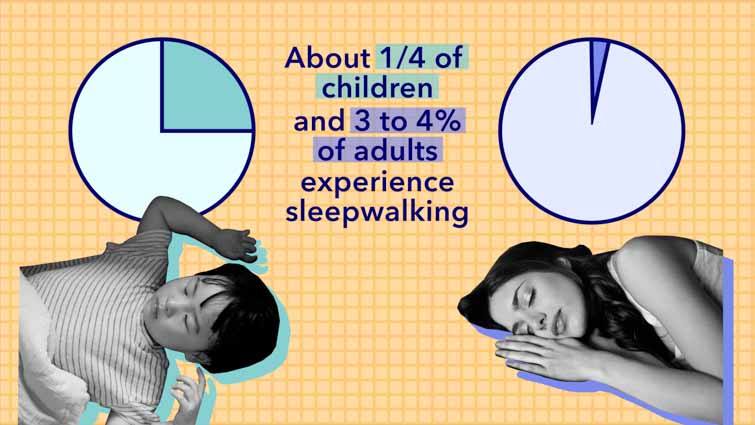

More than 8 million Americans, or nearly 7% of the population, sleepwalk. (7) About a quarter of children will experience sleepwalking and about 3 to 4 percent of adults will experience it. It typically happens during deep sleep, but it can also take place during lighter sleep stages. Most episodes of sleepwalking last ten minutes or less, but they can also be a few seconds or thirty minutes or longer.

Note: The content on Sleepopolis is meant to be informative in nature, but it shouldn’t take the place of medical advice and supervision from a trained professional. If you feel you may be suffering from any sleep disorder or medical condition, please see your healthcare provider immediately.

Symptoms of Sleepwalking

Sleepwalking is most common in children, but does occur in adults. (1) Symptoms of sleepwalking can involve more than just walking during sleep, and may include:

- Sitting up in bed

- Walking

- Lack of responsiveness to a voice or touch

- Leaving the home

- Trying to drive

- Appearing dazed

- Repeating certain movements such as rubbing the eyes

The majority of the time, these tendencies go away when people get more sleep or a higher quality of sleep.

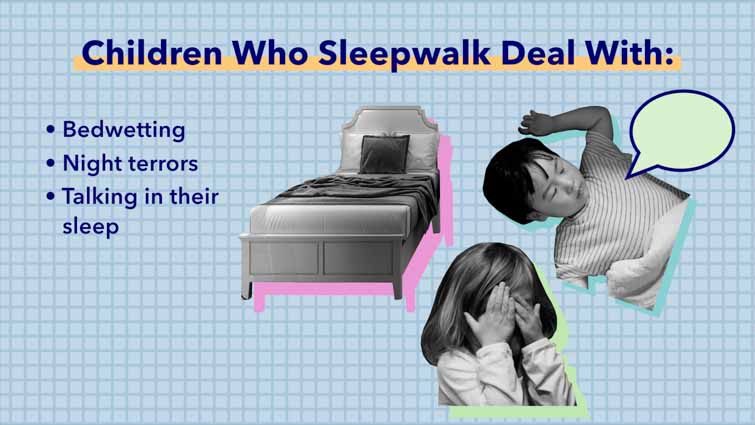

Children who sleepwalk may experience other parasomnias, as well, including bedwetting, night terrors, and talking in their sleep. (2) Common effects of sleepwalking in children include daytime sleepiness, behavioral issues at home or school, and symptoms typically associated with ADHD, such as difficulty concentrating and hyperactivity.

The Dangers of Sleepwalking

Sleepwalking is a disorder of “partial arousal,” meaning the sleeper is not fully awake and alert. (3) It occurs during the deepest stage of sleep, also known as N3 or slow wave sleep. Blood flow to the brain decreases during N3 sleep and is redirected to other parts of the body for tissue repair and maintenance of the immune system. Lack of cerebral blood flow makes waking up during N3 sleep difficult, even when sleep is disturbed.

Sleepwalking can become dangerous when the sufferer attempts to engage in activities that require full consciousness and coordination. These may include:

- Leaving the home

- Using stairs

- Driving

- Using sharp or heavy objects

- Attempting complex tasks

Sleepwalkers may also open or try to leave the home through a window, rearrange furniture, or run, jump, or climb. In some cases, sleepwalkers may become violent or act out sexually during episodes. Sleepwalking sufferers may have no memory of the incidents, or may be able to remember them in detail.

Try doing the following if you want to wake a sleepwalker:

- Stand to the side of the sleepwalker

- Slowly and gently put your hand on them

- Start talking to the sleepwalker and tell them to wake up, where they are, and that it’s time to go back to bed

Waking a sleepwalker may be difficult, but can help keep them from injuring themselves. To protect children and adults who sleepwalk, try the following tips:

- Make sure front and back doors are locked at night

- Install childproof locks on windows

- Don’t allow a child who sleepwalks to sleep in a top bunk bed

- Put heavy, sharp, or dangerous objects out of reach

- Hide keys if the sleepwalker has ever attempted to drive

- To prevent falls, install gates on stairways

- If episodes continue, see your healthcare provider for professional diagnosis and advice

What Causes Sleepwalking?

Sleepwalking occurs more often in children whose parents sleepwalked as children, indicating a possible genetic link. (4) The sleep and wake system is less mature in children, which may contribute to sleepwalking episodes.

One of the biggest causes of sleepwalking is not getting enough sleep on a routine basis. Sleep deprivation can happen as a result of too much caffeine, drinking alcohol close to bedtime, taking long naps during the day, and can even stem from anxiety or stress.

Other potential causes include:

- Fever or illness

- Trauma or PTSD

- Jet lag or other disruptions to the circadian rhythm

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Other sleep disorders, such as restless legs syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea (5)

- Use of alcohol, recreational drugs, and certain medications, particularly prescription sleep medications and sedatives

- Stress and major life changes, such as a move or loss of a family member

Many cases of sleepwalking have no clear cause, particularly in children. Sleepwalking typically appears in childhood, but in most cases resolves without treatment by adolescence. Most cases occur only occasionally and are not an indication of an underlying disorder.

Sleepwalking Treatment

In most cases of sleepwalking, treatment isn’t necessary. For children and adults who sleepwalk frequently or endanger themselves, however, medication or another type of intervention may help. (14) Treatment may also be warranted in cases that involve the following:

- Another parasomnia, such as night terrors or bedwetting

- Another sleep disorder, such as sleep apnea or narcolepsy

- Significant awakenings during the night that result in daytime sleepiness, impaired function, or behavioral issues

Treating underlying medical or sleep issues can help reduce the tendency to sleepwalk and improve the quality of sleep as a whole. Hypnosis may also be an option for some people who sleepwalk chronically.

A doctor can help determine if treatment is necessary and what will be the most effective approach. Addressing any underlying causes is the first step. This may include starting or switching medications. Other steps may include self-hypnosis or waking up a person who regularly sleepwalks 15 to 30 minutes before an episode would normally start. This is called anticipatory or scheduled awakening, and the individual should be kept awake for approximately 15 minutes before being allowed to go back to sleep. (6)

Scheduled awakenings can also help prevent night terrors, a parasomnia characterized by overwhelming fear and physical symptoms, such as sweating and dilated pupils.

Medications

Medications are not typically prescribed for sleepwalking unless the disorder presents a persistent danger or interferes with daily life. Medications for sleepwalking include antidepressants and benzodiazepines, such as:

- Trazodone

- Estazolam

- Clonazepam (Klonopin)

All of these medications may cause side effects like drowsiness and dizziness. Because benzodiazepines can cause dependency and protracted withdrawal symptoms, they are rarely suggested for long-term use.

How to Prevent Sleepwalking

Not all cases of sleepwalking are preventable, but some may be helped by promoting healthy sleep and basic sleep hygiene. Sleep hygiene essentials include:

- Consistent sleep and wake times

- Turning off electronics such as phones, televisions, and video games at least an hour before bed

- Eliminating consumption of caffeine and alcohol at night

- Reducing stress to help deactivate the nervous system

- Practicing mindfulness, meditation, and/or yoga to help decrease anxiety

- Keep the bedroom dark, cool, and quiet

- Have other sleep disorders such as insomnia and sleep apnea treated to help avoid disturbed sleep that might lead to sleepwalking

If sleepwalking and the risk of injury persist, see your healthcare provider to discuss treatment options.

Last Word From Sleepopolis

Sleepwalking is a potentially dangerous sleep disorder that can result in injury, daytime sleepiness, and behavioral issues. Though sleepwalking often occurs only occasionally and resolves on its own, it can pose a risk of injury or death.

Addressing underlying disorders that may contribute to sleepwalking can help reduce episodes of sleepwalking. People with a family or personal history of leaving the home or putting themselves in jeopardy may lower the chance of injury by maintaining healthy sleep habits and seeking treatment from a medical professional.

References

- Antonio Zadra, Somnambulism: clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses, The Lancet Neurology, March 1, 2013

- Fleetham JA, Fleming JA., Parasomnias, Canadian Medical Association Journal, May 2014

- Robyn Mehlenbeck, The clinical presentation of childhood partial arousal parasomnias, Sleep Medicine, October 2000

- Dominique Petit, Childhood Sleepwalking and Sleep Terrors: A Longitudinal Study of Prevalence and Familial Aggregation, JAMA Pediatrics, July 1, 2015

- Helen M Stallman, Assessment and treatment of sleepwalking in clinical practice, Australian Family Physician, Chronic Illness in Adolescents, 2017

- Drakatos P, Marples L, Muza R, Higgins S, Gildeh N, Macavei R, Dongol EM, Nesbitt A, Rosenzweig I, Lyons E, d’Ancona G, Steier J, Williams AJ, Kent BD, Leschziner G., NREM parasomnias: a treatment approach based upon a retrospective case series of 512 patients, Sleep Medicine, January 2019

- Stallman HM, Kohler M., Prevalence of Sleepwalking: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Plos One, November 10th, 2016

- Christian Guilleminault, Adult chronic sleepwalking and its treatment based on polysomnography, Brain, May, 2005

- Mary Grace Umlauf, Bedwetting—Not Always What It Seems: A Sign of Sleep‐Disordered Breathing in Children, Pediatric Nursing, February 22, 2007

- Popat S, Winslade W., While You Were Sleepwalking: Science and Neurobiology of Sleep Disorders & the Enigma of Legal Responsibility of Violence During Parasomnia, Neuroethics, April 2015

- Christian Guilleminault, Non-REM-sleep instability in recurrent sleepwalking in pre-pubertal children, Sleep Medicine, November 2005

- Elana R. Bloomfield BA, Parasomnias and Movement Disorders in Children and Adolescents, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, October 2009

- Frank NC, Spirito A, Stark L, Owens-Stively J., The use of scheduled awakenings to eliminate childhood sleepwalking, Journal of pediatric psychology, June 1997

- Bharadwaj R, Kumar S., Somnambulism: Diagnosis and treatment, Indian journal of psychiatry, April-June 2007