Sleep Better. Choose Smarter.

Thousands of expert-tested mattress reviews, tools, and advice for your best night’s sleep.

Explore By Category

Need Help Finding the Perfect Mattress?

Need help finding the right mattress?

Best Mattress Roundups

Find the Best Mattress For You

We’ve done the testing so you can sleep easy.

10 Best Mattresses of 2026: Over 500 Tested by Sleep Experts

Updated: March 3, 2026The 11 Best Mattresses for Heavy People, Expert-Tested and Reviewed

Updated: March 3, 2026Best Mattress for Back Pain

Updated: March 2, 2026The Best Mattress for Couples: Expert Tested to Help You Reach Couples Goals

Updated: March 2, 2026The Best Firm Mattresses: 10 Expert-Tested and Reviewed Beds (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Soft Mattress: Expert Tested and Reviewed

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Bed in a Box Mattresses (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Cooling Mattress for Hot Sleepers

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for Kids (2026): Bedtime Made Better with Our Top Picks

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattress in Canada

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattress for Sex (2026): Based on Responsiveness, Cooling, and Edge Support

Updated: March 2, 2026The Best Mattresses for Seniors: Tested and Reviewed by Experts

Updated: March 2, 2026The 9 Best Mattresses For Athletes: Doctor and Sleep Science Coach Tested

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for Teens (2026), Comfort That Grows with Them

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Hypoallergenic Mattress (2026): Say Sayonara to Nighttime Sniffles

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattress for Pregnancy (2026): Contouring, Supportive, and Cooling

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for Side Sleepers (2026): Expert Tested & Reviewed

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for Back Sleepers: Reviewed and Tested by Sleep Experts (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattress for Combination Sleepers

Updated: March 2, 202610 Best Mattresses for Hip Pain (2026): Tested and Approved by Experts

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattress for Neck Pain (2026), Our Top Picks for the Stiff and Sleepless

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for Sciatica (2026), Expert-Tested for Pain Relief and Spinal Support

Updated: March 2, 202610 Best Mattresses for Shoulder Pain (2026): Expert-Reviewed & Doctor Approved

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for Stomach Sleepers: Firm, Supportive Beds Tested and Reviewed by Experts

Updated: March 2, 2026Best King-Size Mattress (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Queen Size Mattress (2026): Based on 330 We Tested

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Organic and Natural Mattress (2026): Free from Harmful Chemicals and Toxins

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Innerspring Mattress (2026): Tested by Sleep Experts

Updated: March 2, 2026After Testing 132, Here Are The 10 Best Memory Foam Mattresses (2026)

Updated: March 3, 2026Best Hybrid Mattresses (2026): Sleep Better with These Top Picks

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Latex Mattress

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Pillow-Top Mattress (2026): Expert-Tested for Quality

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Cheap Mattresses (2026): Top Budget Picks From Sleep Experts

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Hotel Mattress (2026), Five-Star Comfort for All Four Seasons

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Amazon Mattress (2026), Comfort Delivered to Your Doorstep

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses for the Money (2026): High-Quality and Affordable Pricing

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattresses Made in the USA (2026), High-Quality Manufactured at Home

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Mattress for Arthritis (2026): Expert-Tested to Help Ease Arthritis Pain

Updated: March 3, 2026Best Flippable Mattress 2026 – Expert Reviewed & Tested

Updated: March 2, 2026Best Luxury Mattresses (2026): Premium Comfort That’s Worth the Money

Updated: March 2, 2026Mattress Reviews

See What Makes Each Mattress Unique

Get the features, feel, and facts — all in one place.

Helix Midnight Mattress Review (2026): Certified Sleep Science Coach Tested

Updated: March 2, 2026Saatva Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Casper Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Nolah Original Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: February 17, 2026Nectar Classic Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Purple Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: February 24, 2026WinkBeds Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Tempur-Pedic Mattress Reviews 2026

Updated: March 2, 2026Layla Flippable Memory Foam Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Bear Original Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: February 24, 2026Puffy Cloud Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Amerisleep Mattress Reviews

Updated: February 24, 2026Saatva Loom & Leaf Mattress Review (2026), Luxurious and Eco-Conscious Comfort

Updated: March 2, 2026Zinus Green Tea Memory Foam Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Novosbed Mattress Review

Updated: March 2, 2026Tuft & Needle Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: February 24, 2026Casper Hybrid Mattress Review

Updated: March 2, 2026Bear Elite Hybrid Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Purple Restore Mattress Review

Updated: March 2, 2026Brooklyn Bedding Signature Hybrid Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Tuft and Needle Hybrid Mattress Review

Updated: December 3, 2025Nectar Luxe Hybrid Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026DreamCloud Premier Hybrid Mattress Review 2026

Updated: February 24, 2026Puffy Lux Hybrid Mattress Review

Updated: March 2, 2026Avocado Green Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Zenhaven Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Birch Natural Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Awara Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026PlushBeds Botanical Bliss Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Brentwood Home Cedar Natural Luxe Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Saatva Latex Hybrid Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: February 24, 2026WinkBeds EcoCloud Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026DreamCloud Hybrid Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Leesa Original Mattress Review (2026): Tested by a Certified Sleep Science Coach

Updated: February 24, 2026Simmons Beautyrest Black Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Helix Luxe Mattress Reviews 2026

Updated: March 2, 2026Saatva Rx Mattress Review (2026): Doctor and Certified Sleep Science Coach Tested

Updated: March 2, 2026WinkBeds Mattress Review (2026)

Updated: March 2, 2026Saatva Solaire Mattress Review

Updated: February 24, 2026Brooklyn Bedding Plank Firm Mattress Review (2026)

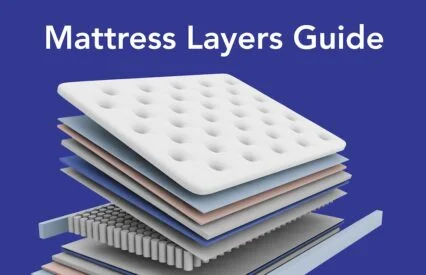

Updated: March 2, 2026How We Test Mattresses

Here at Sleepopolis, we only recommend beds that we’ve tested personally. We’ve brought hundreds of mattresses to our lab, where our team of experts gathers to evaluate each by collecting and comparing 50-plus distinct data points.

Full Team of Experts

Our team is made up of Certified Sleep Science Coaches and industry experts with years of hands-on experience with mattresses and sleep products. Whenever possible, we have multiple people with different body types and comfort preferences evaluate a given bed. We also consult with a network of physicians, physical therapists, nurses, and other medical professionals to verify our findings and ensure we’re providing helpful, health-focused recommendations.

Purpose-Built Mattress Lab

We use specialized tools to collect readings on critical aspects of a bed’s performance— temperature, pressure relief, motion isolation, and more—in an environment designed for repeatable, reliable testing. These results are compared and contrasted with notes on how a mattress really feels and performs according to our in-house testers.

13 Data-Driven Tests

Each of our tests is scored individually and then combined on a weighted scale that determines a mattress’s overall rating, which is numbered from 1 to 5. All of these scores then inform our mattress recommendations for specific kinds of sleepers, such as dedicated side sleepers, people with sleep apnea, and folks who prefer a very firm bed.

The Core Tests Behind Every Review

Every mattress we review is put through the same 13-point set of comprehensive tests. Below are some of the most important ones that impact sleep quality and long-term comfort.

Firmness

Rated on a 1 to 10 scale, with 1 being the softest and 10 being the firmest.

Pressure Relief

Measured with a pressure-mapping mat to see how evenly weight is distributed.

Edge Support

Scored out of 5 based on sitting, lying near the edge, and weight-plate tests.

Cooling

Scored out of 5 with surface temperature readings taken by a thermal gun.

Motion Isolation

Scored out of 5 using water-ripple, partner, and rolling tests.

Responsiveness

Scored out of 5 using real tester feedback and a timed kettlebell snap-back test.

Tools for Better Sleep

Use our calculators to fine-tune your best night’s sleep.

Swipe to view more

Sleep Debt Calculator

Check your sleep debt, learn how to catch up, and prevent future fatigue.

Jet Lag Calculator

Adjust your sleep schedule before travel to avoid jet lag. Land feeling rested and alert.

Sleep Cycle Calculator

Find your ideal bedtime and wake time based on sleep cycles. Wake up refreshed and ready for the day.

Kids’ Sleep Calculator

Enter your child’s age and wake time for expert-recommended bedtimes.

Sleep Education

Sleep Smarter, Live Better

Explore expert tips, science-backed advice, and sleep guides built to help you rest your best.

What is Sleep?

The pace and priorities of modern society have led many of us to believe that rest and downtime are optional. Work, family, and school schedules may seem to require more hours than exist in a day, often leading us to steal time from one of our most essential biological functions: sleep. Sleep is an altered […]

How Sleep Affects The Body

Sleep may appear to be as simple as feeling tired, lying down, and nodding off. But the physiological state of sleep is created by a complex interplay of processes in the brain and body, beginning with signals from the circadian rhythm’s master clock. While sleep originates in the brain, it is a body-wide experience that […]

Why Do We Sleep?

We all know how we feel when we sleep well, and when we don’t sleep enough. When we sleep, we’re happier, we have more energy, and learning comes more easily. When we don’t sleep, we feel unfocused, exhausted, and irritable. We can feel the effects of sleep on our brains and bodies, but we may […]

Sleep Stats & Facts

We may be out for the count and largely unaware of what’s happening around us while we sleep, but our bodies remain busy with myriad biological housekeeping functions. And while most people are well aware that sleep is a cornerstone of health and well-being, it seems that daily life in the 21st century, hustle culture, […]

The Genetics of Sleep

Sleep is a universal physiological drive with similar processes and rhythms across the human species. Though sleep follows a recognizable pattern, there are numerous differences among healthy individuals. Though some of these differences are environmental and relate to meal times, travel schedule, and work routine, many are inherited. Whether you’re an early bird, a night […]

Sleep Disorders: Typical Causes and Information

How much do we really need sleep? A lot, it turns out. Sleep rejuvenates our bodies and minds, gives our immune system a major boost, and repairs and builds tissues throughout the night. (1) Sounds pretty amazing, right? When sleep disorders steal your sleep, you can feel sluggish, cranky, and forgetful. We’re going to tell […]

Insomnia: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments

Do you ever have trouble sleeping? At one time or another, most of us have experienced bothersome symptoms of insomnia: difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or both. We may have lived through bouts of insomnia that last a few days, or much longer. Though the symptoms may seem simple enough, insomnia is a complex condition […]

Sleep Disorders in Children

Most children hate sleep at certain points in their development — life feels too full of adventures, games, and delicious snacks to waste time sleeping! In J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, Wendy, Peter, and Michael’s canine nanny was trying to put them down for the night, but little Michael hollered, “I won’t go to bed!… I […]

Sleep Apnea And Memory Loss

Do you get punched at night for deafening snores? Or wake up feeling tired even though you think you got plenty of sleep? These signs could point towards sleep apnea, a common sleep disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. Sleep apnea not only disrupts your sleep but also affects your brain function and memory. […]

Types of Insomnia

Insomnia can steal just a few night’s sleep, or it can hang around for years. Over the decades, experts have categorized and re-categorized the different types of insomnia, and while all insomnias fall under three main umbrellas now, your specific insomnia may also be in a subcategory. Figuring out your own special blend of sleeplessness […]

How To Get Better Sleep

Sleep is essential for optimal well-being, and impacts everything from mood to muscle strength to memory. Despite the importance of adequate rest, many people don’t get consistent healthy sleep. Poor sleep can be associated with numerous physical and emotional factors, including stress, medications, medical conditions, and poor diet. The most common sleep difficulty in the […]

Magnesium vs. Melatonin

Melatonin as a mainstream sleep aid has long been accepted — promising sound, natural sleep, touted as a “miracle” for people with sleep disorders. But in recent years, magnesium has taken the spotlight, claiming that it promotes more restful sleep and improves sleep longevity with fewer negative side effects compared to melatonin. So does it […]

Are Alarm Clocks Bad For Sleep?

Could hitting “snooze” be bad for your sleep hygiene and overall health?

The Benefits of Napping

Find out why naps could have big impacts beyond just feeling rested!

Is Melatonin Safe?

Here’s what you need to know about the powerful hormone melatonin and its role in sleep.

Sleep & Heart Health

We all need a heartbeat to survive, and quality sleep also plays a vital role in our overall health. But did you know sleep and heart health are connected? It’s true — how well you sleep through the night can have an impact on your cardiac function, and vice versa. (1) More than one third […]

Weight Loss and Sleep

So, you’re doing everything right to lose weight: meticulously counting calories and hitting the gym. Yet the scale won’t budge! Certain health conditions, genes, and even side effects of medications could be part of the problem. (5) But here’s something you might not have considered: your sleep habits could be sabotaging your weight loss efforts. […]

Exercise & Sleep

The solution to a more restful night? Movement, experts say. It seems the answer to so many physical and mental health woes have just one thing in common — exercise. Sleep is no exception. If you are looking for longer sleep, higher-quality sleep, or fewer interruptions from sleep apnea, insomnia, and other ailments, the type […]

Health Benefits of Sleep

We may all have our differences, but every human in the world needs sleep. Why is sleep important? Every system in your body relies on good sleep to recover from the day and get ready for the next one. (7) The benefits of sleep include better immune health, easier weight management, a healthier heart, improved […]

How To Sleep With Lower Back Pain

Picture it: You’ve just woken up after a horrendous night of sleep, your night of rest disrupted by the relentless nagging of lower back pain. Many of us can relay a similar story, whether your back pain is triggered by a longstanding problem or an acute injury that’s baring its teeth whenever you try to […]

Athletes And Sleep

Most of us are no stranger to the phrase “be sure to get a good night’s sleep” — especially the night before an event that requires us to be at our best, like an important presentation or test (1). Athletes of all levels are no exception: Getting adequate sleep pays off just as much in […]

Sleep Hygiene Guide

How well do you set yourself up for successful sleep? If you’ve never heard of sleep hygiene, the term might sound odd. But having good sleep hygiene has nothing to do with keeping you clean. Sleep hygiene describes lifestyle choices that promote quality sleep. When you know how to do it, you may notice you […]

Is 6 Hours of Sleep Enough?

While you may look forward to crawling into bed and getting some much-needed sleep, part of you may wish you needed less of this essential habit. How many people have dreamt of somehow having more hours in the day? Sometimes it may seem that the easiest way to add time to your life would be […]

What Are Dreams?

The mystery of dreams has captivated people for millennia. And while life in the 21st century (and the unprecedented access to information that comes with it) leaves us with relatively few mysteries, some questions remain. Take sleep and dreams, for example. With all we know about sleep, questions about the purpose and nature of dreams […]

Why Am I So Tried After Lunch?

Most of us are intimately acquainted with the afternoon slump, when we struggle with zapped energy and an almost unbearable desire to curl up for a nap. But what’s really going on? Why are we so tired after lunch? We tapped three sleep experts for a little insight, plus their tips for staying alert until […]

Meet the Sleepopolis Team

Real people. Real expertise. Our editors, testers, and sleep coaches are here to guide you toward better rest with honest insights and first-hand experience.

Licensed Clinical Psychologist

Chief Medical Advisor and quadruple-board certified in pulmonary, sleep, internal, and critical care medicine

Matt Schickling

Head of Content, Commerce

Senior Editor and Certified Sleep Science Coach

Senior Staff Writer and Certified Sleep Science Coach

Staff Writer and Certified Sleep Science Coach

Staff Writer and Certified Sleep Science Coach

Sales – Coupons & Promos

Unlock the Best Mattress Deals

Save big on top-rated mattresses — handpicked for you.

Saatva Classic

Helix Midnight Luxe Mattress

Leesa Sapira Chill Hybrid

Nectar Mattress

DreamCloud Original Mattress

WinkBed Mattress

Ready to Find Your Perfect Mattress?

Take our quick quiz and get personalized mattress recommendations.