Now the host of a sleep podcast, and after a lifetime of sleep apnea symptoms and dismissive doctors, it took falling asleep at the wheel with her baby in the back seat for Emma Cooksey to push for the diagnosis she knew was coming. Here, she shares with Sleepopolis writer Sharon Brandwein what it was like to go from sleepy and ignored to life with a CPAP machine and a mission to help others.

The biggest misconception about sleep apnea is that it only affects overweight, middle-aged men. That’s probably why so many women of all ages are under-diagnosed with the condition. I probably had undiagnosed sleep apnea for most of my twenties. And it took falling asleep at the wheel with my baby in the backseat to get one.

For as long as I can remember, I had all the symptoms. They weren’t mild or fleeting. They were present each and every day of my life. I was tired. I was sleepy during the day. I had anxiety, depression, and irritability was almost normal.

Each time my symptoms became unbearable, I went to the doctor. Each time, I told them I was tired, so tired that maybe there was something wrong with my sleep. Each time they told me, “you’re a young woman,” “you’re fit,” and “sleep disorders are rare” — “go home.”

The circle of symptoms and dismissals worsened after the birth of my first child. The early days were what they were — the same for every new mom, no sleep. But by the time my daughter was 7 months old, she was sleeping through the night. I knew that I had a window every night where I should have been able to sleep. But, every morning, I woke up just as tired as I was the night before, maybe even more so. And I had all these different symptoms — morning headaches, waking up a lot at night and gasping, and just feeling really anxious all the time. So back to the doctor I went.

This time I tried a preemptive strike on their flippancy. I told the doctor, “I know you’re going to say, ‘I have a new baby,’ but that’s not what this is. My baby is sleeping through the night, and I still feel terrible.” I’m not sure what I expected, but like all the other times before, I was dismissed. This time, the doctor said, “People don’t realize how exhausting looking after a newborn is.” The end result of that visit was, “You have a new baby — go home.”

Three weeks later, I took my daughter to see my mother-in-law, who lived about 30 minutes away. On the way home, I got on the Buckman Bridge in Jacksonville. And as soon as I got on the bridge, I felt this overwhelming sleepiness. I did everything I could to stay awake — I blew air in my face and sang songs.

At one point, I was looking at the truck in front of me and trying to make out the license plate, and the next thing I knew, the license plate that had been really far away was suddenly coming toward me. I had to slam on my break to avoid hitting the truck. By some miracle, we weren’t injured, but that was the wake-up call I needed to realize this was really serious. I felt sleepy before while driving, but this was the first time with my baby in the car, which really upset me.

I went home, handed my daughter over to my husband, and immediately called the doctor. I told her, “I just fell asleep at the wheel; I think there’s something wrong with my sleep.”

Things started happening from there, and I wish I could say it was smooth sailing, but it really wasn’t. I had every problem with CPAP you could possibly have. For some people, the CPAP changes their life overnight, but that wasn’t my experience.

The doctor referred me for a polysomnogram. A sleep tech came out to my home, wired me up with electrodes all over my head and body, and a cannula in my nose to measure airflow — basically, if there was anything wrong with my sleep, they were going to find it. The strangest part of the process was that another sleep tech was watching me sleep from a laptop in Texas.

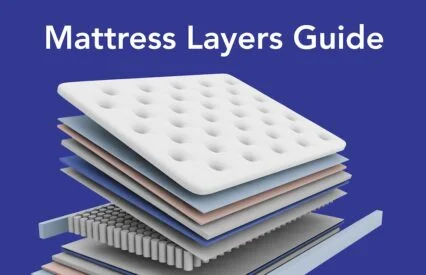

The polysomnogram confirmed it. At that point, I had never heard of sleep apnea, but in 2008, I was diagnosed with moderate obstructive sleep apnea. One thing that stands out in my memory is that the doctor was surprised that a woman and a young mom who didn’t have many of the risk factors for sleep apnea would have this disorder. He was really quite shocked. But he also said, “Don’t worry, we have this thing called the CPAP machine, and you’ll be feeling better in no time.” I left his office that day with a diagnosis and a prescription in hand for a machine I didn’t know how to use. I went to the DME company next door, and the lady pretty much just gave me the machine in the bag and said, “Bye-bye.”

This was 2008, and the only resource I had for answers were internet chat rooms and forums. The internet wasn’t anywhere close to what it is now. For us internet pioneers, Google wasn’t “Google” back then, and YouTube was just getting off the ground. So I found myself on the internet almost daily trying to find answers to things. As primitive as they seem now, those chat rooms and forums were how I figured out that I needed a humidifier, that I could change comfort settings on my CPAP, and the biggest issue of all, that I had a mask that didn’t fit my face.

It took me a couple of months to work out the kinks, and when all the issues were finally resolved, I found that I would wake up less during the night, and the intense daytime sleepiness got better. I never had that feeling again, like I wanted to fall asleep at the wheel, so I make sure that I’m consistent with it. When my sleep apnea was untreated, I dealt with a lot more anxiety and depression, too. I still deal with those things today, but they’re managed a lot better, and overall my quality of life is a lot better.

Some people think it has to be awful to sleep with a mask that’s attached to a hose that’s attached to a machine on your bedside table, but over time, you just get so used to it. It becomes a part of your bedtime routine. After years of using it, I don’t really think about it too much. In addition to using the CPAP, I also sleep on my side and elevate my bed, so my CPAP doesn’t have to do as much work. What most people don’t quite understand (or don’t know) is that CPAP is just a part of the equation. Doing things like sleeping on your side, elevating your head, watching your diet, minimizing inflammation, and managing your weight all play a role in sleep apnea management, so it’s not just the CPAP machine on its own.

As women, we’ve normalized being exhausted all the time. So, on the whole, there are not enough women seeking treatment for all sorts of issues and sleep problems.

Emma Cooksey

This entire experience inspired me to start my weekly podcast, Sleep Apnea Stories, in 2020.

The first issue was that I wasn’t diagnosed because I didn’t fit the profile. So many people have never heard of sleep apnea; if they have heard of it, it’s something that their grandpa or an older male relative had. It never seems to happen to a young woman in her 30s.

And in addition to doctors not screening for the disorder because someone doesn’t check a few boxes, I think, as women, we’ve normalized taking on way too much and being exhausted all the time. So, on the whole, there are not enough women seeking treatment for all sorts of issues and sleep problems. I think that doctors and the general public need to catch up on their perception of who has sleep apnea.

Going through the process, I also noticed that there’s a disconnect between all of the providers you need to see to get a diagnosis and treatment. The company that does the sleep study is different from the sleep specialist who interprets the results, and both are separate from the doctor who prescribes the CPAP, and they’re all separate from the DME company that supplies it. I really think that’s where people tend to fall through the cracks; there’s no joint effort or continuity of care to help people in the early stages of a sleep apnea diagnosis.

Before I started the podcast, I read an article that was talking about oral appliance therapy, Inspire implants, and different surgical procedures for sleep apnea, and I thought, Why wasn’t I told anything about these treatments for the 12 years that I had sleep apnea? And the thing that’s unique about sleep apnea is that people need to access different providers for all those different treatments, so navigating a sleep apnea diagnosis can be super difficult.

Sleep Apnea Stories is in its third year. The thing I’m most proud of is just being able to interview people from all different specialties and patients from diverse backgrounds who have used different treatment approaches. Putting it all in one place is really helpful to people who are listening. CPAP isn’t for everybody, and doctors don’t necessarily know how to connect people with the treatments they need. Providing that information makes me feel really good about what I’m doing.

Also, I felt a lot of shame and embarrassment when I was diagnosed because everything I read connected this condition with older, overweight men. I had never heard of anyone my age dealing with it. So, I don’t remember ever talking to the young moms that I knew about it, and I never told anyone about being diagnosed with it.

Through the podcast, I feel like I’ve created a community that just didn’t exist before. Over the years, people have been very responsive. I constantly get emails from people saying, “thank you so much for talking about this treatment option. I didn’t know about that, and now I’m going to ask my doctor about it.” Things like that are just priceless.

By doing the podcast, I feel like I have a tribe of so many other people going through the same things. I feel like we’re walking it together rather than alone, which is such a nice feeling.