Insomnia and hypersomnia — the words sound similar, and in a few important ways, they are. Both use the same suffix, which means sleep in Latin. Both are sleep disorders with a neurological basis, and even share some symptoms and triggers.

Both insomnia and hypersomnia can lead to lost productivity, decreased quality of life, and feelings of fatigue and depression. Insomnia increases the risk of cognitive dysfunction and accidents, and so does hypersomnia. Stress can worsen the symptoms of both conditions.

So what’s the difference between these two sleep disorders? Insomnia means no sleep, while hypersomnia means too much sleep.

Though the differences might sound straightforward, they are actually quite complex. The disorders are complex, as well.

Note: The content on Sleepopolis is meant to be informative in nature, but it shouldn’t be taken as medical advice, and it shouldn’t take the place of medical advice and supervision from a trained professional. If you feel you may be suffering from any sleep disorder or medical condition, please see your healthcare provider immediately.

Insomnia and Hypersomnia: Similarities and Differences

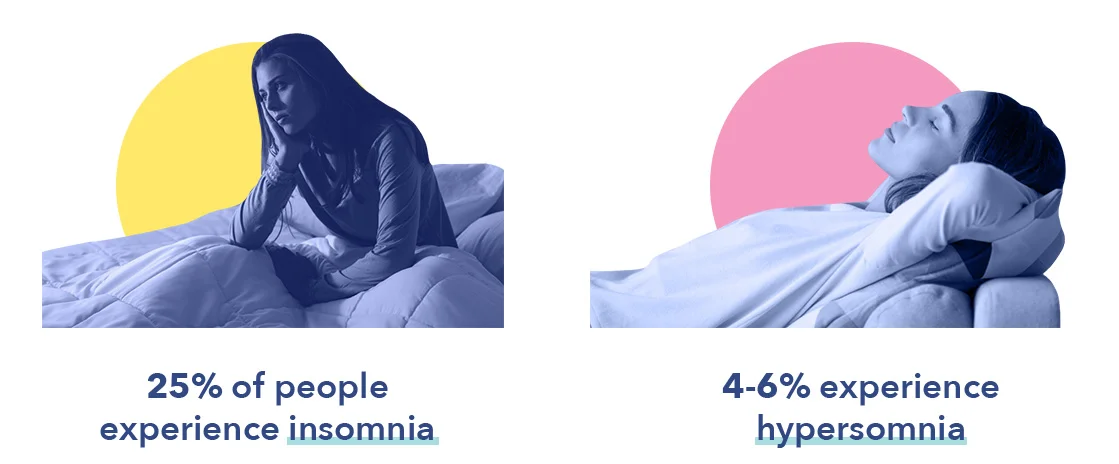

Sleep disorders are found in every country and culture, and the most common of these is insomnia. Nearly all of us have experienced an episode of insomnia at some time in our lives, with 33% of the adult population experiencing chronic insomnia.

Though not as prevalent as insomnia, hypersomnia is also common, affecting 4-6% of the population. More men than women are affected, in part because more men suffer from sleep apnea, a common cause of hypersomnia. There are two recognized forms of hypersomnia — primary, or of unknown cause, and secondary, caused by another condition, drug, or sleep disorder.

Takeaway: While both insomnia and hypersomnia are common sleep disorders, insomnia is experienced far more often.

Symptoms of Insomnia Vs. Hypersomnia

Insomnia symptoms are quite common, and differ from insomnia as a chronic disorder. Though both involve the inability to fall asleep, stay asleep, and/or fall back to sleep, insomnia disorder persists for at least three months, and may not resolve without treatment. Insomnia symptoms typically go away on their own after days or weeks, and do not usually require treatment.

Core symptoms of insomnia may occur at any time of life (1), and typically include:

- Difficulty falling asleep

- Difficulty staying asleep

- Difficulty falling back to sleep

- The inability to sleep even when given the opportunity

In contrast to insomnia, which can occur at any time of life from infancy to old age, symptoms of primary hypersomnia most often begin in childhood or adolescence. Symptoms of secondary hypersomnia, however, typically begin in adulthood, when medical issues and other sleep disorders are most likely to occur.

Core symptoms of both primary and secondary hypersomnia include:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness

- Extended time spent sleeping

- The need to nap after sufficient sleep

- Feeling drowsy despite adequate rest

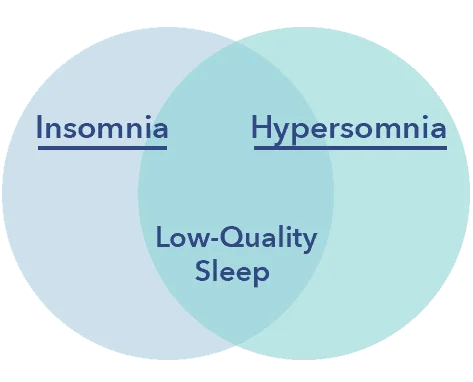

Though the symptoms of insomnia and hypersomnia appear to be markedly different, the disorders have a few possible symptoms in common: fragmented and low-quality sleep. Fragmented sleep refers to frequent awakenings that interrupt sleep cycles, leading to less time spent in the deeper, more restorative stages of sleep. Fragmented, low-quality sleep may be due to sleep-wake disturbances in the brain in both disorders, and/or hyperarousal of the nervous system in insomnia.

While the symptoms of insomnia are similar no matter what the cause, hypersomnia symptoms may vary widely depending on the underlying etiology. For example, people who suffer from the form of hypersomnia called narcolepsy may experience parasomnias such as sleep paralysis, along with cataplexy, a sudden weakness of the muscles associated with strong emotion and laughter.

Such symptoms rarely if ever occur with secondary hypersomnia caused by another medical condition or drug side effect. People with secondary hypersomnia are more likely to experience such symptoms as excessive daytime sleepiness, difficulty waking from sleep, and cognitive dysfunction.

Takeaway: Though insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms may appear to be quite different, both can result in fragmented and low-quality sleep, perhaps due to dysfunction of sleep-wake processes in the brain

Effects

The effects of both insomnia and hypersomnia may vary by duration and severity of the disorder. Short-term symptoms are typically less severe in both disorders, though in both, symptoms may become chronic and more difficult to manage.

The short-term effects of insomnia may include:

- Fatigue

- Reduced ability to learn and concentrate

- Increased hunger

- Poor emotional control

- Decreased motivation

The short-term effects of hypersomnia may include:

- Depression

- A persistent feeling of grogginess

- Trouble concentrating

- Difficulty waking up

- Reduced muscle strength and lung capacity due to immobility

Long-term consequences of insomnia and hypersomnia may be remarkably similar. Both disorders can have numerous detrimental health effects, including impacts on mood and long-term changes to the body’s metabolism.

Other adverse effects of sleeping too much or too little include:

- Depression

- Memory difficulties

- Lack of energy

- Trouble concentrating

- Reduced productivity

- Diminished quality of life

- Disrupted sleep-wake cycles

Both chronic insomnia and hypersomnia may affect brain functions essential for learning, memory, and attention, but by different mechanisms. Chronic insomnia may damage neurons used for these important purposes, while the lack of stability between the brain’s sleep-wake functions may be at the root of cognitive disturbances in hypersomnia sufferers.

Sleep-wake functions may also be disrupted in chronic insomnia due to lack of coordination in parts of the brain that control the actions of falling asleep and waking up. These functions may be influenced by stress, genetics, or external factors such as light and noise. Some researchers believe that chronic insomnia may be due to the activation of both the brain’s sleep and wake states at the same time.

Takeaway: Though short-term effects of hypersomnia and insomnia vary somewhat, long-term effects are quite similar, and include cognitive dysfunction, metabolism changes, loss of memory, and emotional difficulties such as depression

Diagnosis of Insomnia Vs. Hypersomnia

An insomnia diagnosis rarely includes sleep studies, relying instead on the patient’s reporting of symptoms. A sleep diary and responses to the Insomnia Severity Index may also be of benefit. Rarely are other tests needed or performed.

A diagnosis of hypersomnia is typically more complex, and might require a questionnaire such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, as well as a physical examination to rule out other causes of the disorder. Additional testing may include an MRI to look for other possible neurological causes and a polysomnography, a sleep test that records brain waves, eye and leg movements, and levels of oxygen in the blood.

Takeaway: Hypersomnia may be more complex to diagnose than insomnia, and might include sleep studies, questionnaires, imaging, and a physical examination

Treatment

Treatment of insomnia and hypersomnia is typically quite different, though good sleep hygiene may be suggested for sufferers of both disorders if symptoms are relatively mild. Good sleep hygiene includes regular sleep and wake times, as well as a cool, dark, and quiet bedroom, avoiding the use of electronics before bed, and using the bed only for sleep and sex.

Insomnia treatment typically distinguishes between short-term symptoms and insomnia disorder, which is often responsive to a type of therapy called CBT-I. Insomnia medications, both prescribed and over-the-counter, may be used for a limited time under a doctor’s care. Most short-term insomnia symptoms resolve by themselves without treatment.

Treatment of hypersomnia often involves stimulant medications such as those used for Attention Deficit Disorder. Anti-depressants also be prescribed, as well. Flumazenil, which reverses the effects of benzodiazepines, is sometimes used off-label for hypersomnia. Sodium oxybate may also be effective for certain forms of the disorder.

Takeaway: Treatments for insomnia disorder include the CBT-I protocol and medications, while short-term insomnia symptoms often resolve on their own. Hypersomnia treatment may include stimulants and other drugs designed to increase the feeling of wakefulness

Hypersomnia and Insomnia — Closer Than They Appear

Though insomnia and hypersomnia may sound like entirely distinct disorders, a closer examination reveals the striking similarities between sleeping too much and sleeping too little. From causes to long-term physical and emotional effects to impacts on quality of life, there is considerable overlap between insomnia and hypersomnia, despite the differences in what sufferers of the disorders may experience.

For a more thorough understanding of insomnia and hypersomnia, continue reading. We take a deeper dive into the specifics of insomnia and hypersomnia below.

Insomnia and Its Symptoms

Myths abound about insomnia, a disorder so prevalent that fully half the world has experienced it. Or have they? While symptoms of insomnia are common, the disorder itself is much less so.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) defines insomnia disorder as dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality, associated with one or more of the following symptoms:

- Difficulty initiating sleep

- Difficulty maintaining sleep, characterized by frequent awakenings or problems returning to sleep after awakening

- Early-morning awakening with inability to return to sleep

- The sleep disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairments in social, occupational, educational, academic, behavioral, or other important areas of functioning

- Sleep difficulty occurs at least 3 nights per week (2)

- Sleep difficulty is present for at least 3 months

- Sleep difficulty occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep

- The insomnia cannot be explained by and does not occur exclusively during the course of another sleep-wake disorder

- The insomnia is not attributable to the physiological effects of a drug of abuse or medication

- Coexisting mental disorders and medical conditions do not adequately explain the predominant complaint of insomnia

Though insomnia symptoms may last for weeks or even a few months, they usually do not follow the diagnostic criteria for insomnia disorder or chronic insomnia, and may be responsive to positive changes in sleep habits.

Causes of Insomnia Disorder

Until recently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) divided insomnia into two categories: idiopathic, meaning no known cause, and secondary, meaning caused by another condition, medication, or disorder. This definition was updated in 2015 to reflect the current understanding of insomnia disorder, or chronic insomnia, which differs from insomnia symptoms caused by stress, mood disorders, or illness.

Insomnia disorder is almost always a conditioned negative response to sleep, bedtime, and the sleeping environment. (3) This conditioned response may develop after a bout of transient insomnia, when the fear of being unable to sleep becomes a recurrent cycle, and persists despite the removal of the original trigger or stressor.

How does fear of insomnia lead to insomnia disorder? Falling asleep, staying asleep, and falling back to sleep are complex processes that may be disrupted by stress, negative expectations, and anxiety. Over time, the attempt to sleep and the sleep environment, including nighttime rituals such as showering and brushing teeth, may become associated with the inability to sleep, causing anxiety and hyperarousal of the nervous system.

Hyperarousal of the nervous system is frequently a key factor in chronic insomnia, and is characterized by increased heart-rate, cortisol secretion, and brain activity as well as elevated metabolism (4). All are symptoms of an activated nervous system, which may disrupt the regulation of sleep-wake systems in the body.

The nervous system usually quiets and slows down in preparation for sleep, but the nervous systems of people with insomnia remain active and responsive to stress during the day and at night. In people suffering from insomnia, neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine may continue to activate parts of the brain involved in wakefulness, disrupting or preventing sleep.

In addition, insomniacs may be “reactive sleepers” whose sleep-wake systems are easily impacted by stress and anxiety. (5) This reactivity could be the result of genetics, environmental factors such as noise and inconsistent sleep habits, or life circumstances that cause stress.

Causes of Insomnia Symptoms

Most often, insomnia symptoms resolve over time and do not require treatment. Insomnia symptoms that last less than three months and occur fewer than three days each week are not considered to be insomnia disorder, but instead are termed insomnia symptoms.

Insomnia symptoms may be the result of:

- Stress

- Mood disorders such as depression

- Grief or trauma

- Illness or disease

- Chronic pain

- Sleep disorders, like restless leg syndrome and sleep apnea

- Medications, especially those with a stimulant effect, such as ADHD treatments and decongestants

- Alcohol

- Hormonal changes

- Jet lag or daylight saving time

Though treatment of occasional or short-lived insomnia symptoms is typically unnecessary, the negative associations and anxiety related to the symptoms may become chronic (6), contributing to hyperarousal of the nervous system, anxiety, and possible development of insomnia disorder.

Diagnosing Insomnia

Because sleep study subjects typically sleep less than usual due to an unfamiliar environment, these types of studies are generally not helpful for diagnosing insomnia disorder or the source of insomnia symptoms. Reporting of symptoms to a doctor is usually sufficient for diagnosing insomnia, particularly chronic insomnia of long duration that is not related to a precipitating event or other medical condition.

In addition to requesting information about your symptoms, a doctor may:

- Ask about your sleep habits and social environment

- Suggest you keep a sleep diary to track your sleep patterns and identify factors that might contribute to your insomnia issues

- Ask you to take one or more insomnia tests to better understand your sleep habits. These might include questionnaires such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Insomnia Severity Index, The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, or a mental health examination

Effects of Insomnia

The effects of insomnia may depend on the duration and severity of symptoms, and can include:

- Fatigue

- Reduced ability to learn and concentrate

- Irritability

- Depression (7)

- Memory issues

- Increased hunger

- Nodding off, or microsleep episodes

The effects of sleep insufficiency due to insomnia symptoms may be different from those due to sleep deprivation, particularly if insomnia is related to anxiety or other factors that cause hyperarousal of the nervous system. (8) Hyperarousal may blunt some of the feelings of insufficient sleep, even if the physical impacts are similar to those experienced by people who are sleep-deprived.

Though insomnia and sleep deprivation can both result in sleep insufficiency, there are key differences. Sleep deprivation is willingly depriving oneself of sleep. Insomnia is the inability to sleep, stay asleep, or get back to sleep.

A person may experience sleep deprivation due to jet lag, an illness in the family, or late nights studying. Sleep deprivation may be short-term or chronic, but if offered the opportunity, the person who is sleep-deprived is able to sleep. The person suffering from insomnia, however, can’t sleep even when given the chance.

Insomnia concerns sleep quality, while sleep deprivation concerns sleep quantity.

Types of Insomnia

Though insomnia is not typically broken into sub-types by medical professionals or for purposes of diagnosis, it can be helpful to do so to understand how the disorder might be experienced by sufferers. Some sub-types refer to the duration of symptoms, while others refer to medical, developmental, psychological, or other causes.

Examples of some insomnia sub-types include the following:

- Transient insomnia — Insomnia lasting less than one week

- Adjustment Insomnia — A period of insomnia linked to a life event, such as moving or starting a new job

- Drug or Substance-Induced Insomnia — Insomnia caused by drug or medication side effects, abuse, or withdrawal. This includes alcohol, nicotine (9), and common mood disorder treatments such as anti-depressants

- Comorbid Insomnia — Insomnia caused by a medical condition or other sleep disorder such as sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome

- Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood — Insomnia that occurs in young children as a conditioned negative response to bedtime and/or the sleeping environment

- Paradoxical Insomnia — Insomnia that sufferers believe is occurring, but for which there is no objective evidence

- Idiopathic Insomnia — Insomnia with an onset during infancy or early childhood.

Treatment for Insomnia

Treatment for insomnia usually falls into three broad categories: sleep hygiene, CBT-I therapy, and medication. A doctor may suggest one or more forms of treatment, depending on the diagnosed cause of the disorder, age of the patient, or underlying medical condition.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT-I

The Cognitive Behavior Therapy protocol (10) tends to be the most effective treatment for chronic insomnia, or insomnia disorder. Improving sleep hygiene is often inadequate for insomnia disorder, though it may help with mild insomnia symptoms and is a part of CBT-I protocol.

The CBT-I protocol consists of four parts, which include:

- Stimulus control training, or SCT. The goal of stimulus control training is to reduce negative associations with sleep, nighttime rituals such as showering, and the bedroom environment. (11) The SCT protocol can help train the brain to associate a particular environment and time of night with sleep, and break the conditioning that causes delayed, fragmented, or low-quality sleep.

- Relaxation training. The purpose of relaxation training is to help prepare the mind and body for sleep using such methods as meditation, guided imagery, and breathing exercises. Biofeedback may help treat insomnia by teaching patients to control bodily processes that are usually involuntary, such as tenseness of the muscles, heart rate, and blood pressure.

- Cognitive Restructuring. Cognitive restructuring helps people with chronic insomnia change their beliefs about sleep and replace negative associations with positive thinking. A therapist may suggest controlling an over-active thought process by limiting discussions or thoughts about stressful topics to a certain time of day so that evening becomes a time of relaxation.

- Sleep restriction. Sleep restriction limits the time spent in bed to the number of hours normally spent asleep. Restricting time in bed can help increase the efficiency of sleep and reduce episodes of waking during the night. As an example, someone who spends nine hours in bed attempting to sleep but lies awake for three hours may be required to go to bed at midnight and get up at 6 am.

Another avenue of therapy treatment is called paradoxical intention (12), which coaches people with insomnia to stay passively awake and not worry about or attempt to sleep. This treatment may help to decrease conditioned responses to bedtime, such as anxiety and restlessness.

Medication

Most medical professionals do not recommend long-term use of insomnia medications, which may lose effectiveness over time. These medications may, however, be an effective treatment for insomnia symptoms and chronic insomnia if used in a limited way and for a brief period under a doctor’s care.

Common side effects of insomnia medications include daytime drowsiness, memory loss, dizziness, headache, or odd behaviors such as eating while asleep. Some medications also have the potential for abuse and dependency.

There are several classes of medications that treat insomnia (13), such as:

- Antidepressants

- Hypnotics and sedatives such as Ambien and Lunesta

- Antihistamines

- Natural treatments and herbal remedies, including melatonin

Sleeping medications do not typically treat the underlying causes of insomnia, which may persist after medications are stopped. People taking insomnia medications are typically advised to allow time for a full night of sleep, and to avoid driving, operating machinery, and drinking alcohol.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene refers to habits and routines that impact sleep. (14) Good sleep hygiene may be an effective remedy for mild insomnia symptoms. Good sleep hygiene basics include:

- Maintaining a regular sleep-wake schedule

- Using the bed only for sleep and sex

- Limiting daytime naps to one nap of thirty minutes or less

- Exercising regularly to improve sleep quality

- Avoiding blue light exposure from electronics and smartphones in the hours leading up to bed

- Making sure the bedroom stays cool, dark, and quiet

- Refraining from consumption of alcohol, caffeine, or heavy meals in the hours before bed

An improvement in sleep habits can help train the brain to associate a particular environment and time of night with sleep, reset the body’s circadian rhythm, and eliminate disruptions that cause the delayed or poor-quality sleep experienced by insomnia sufferers.

Hypersomnia: When Too Much Sleep Isn’t Enough

While insomnia is the inability to sleep, hypersomnia is the inability to stay awake. Sufferers of hypersomnia may spend as many as sixteen hours a day asleep, but feel as exhausted when awake as someone with chronic insomnia.

Most adults feel rested and perform best when they sleep between seven and nine hours each night. For hypersomnia sufferers, however, no amount of sleep may be sufficient. (15)

Hypersomnia Symptoms

In addition to excessive daytime sleepiness, symptoms of hypersomnia may include difficulty concentrating, a feeling of grogginess, the need to nap despite what is normally considered adequate sleep, and sleep inertia, a feeling of disorientation and drowsiness when waking.

Symptoms of primary, or idiopathic hypersomnia (16) may differ from secondary hypersomnia, and might include cataplexy, a sudden weakness of the muscles associated with laughter or strong emotion, and parasomnias such as sleep paralysis, REM sleep disturbances, and hallucinations.

The diagnostic criteria for hypersomnia described by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) pertain to the primary form of the disorder. Symptoms must occur at least three days each week for three months or longer, and occur despite an adequate time spent asleep (approximately seven hours). Other criteria include:

- Symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness that can’t be explained by an inadequate amount of sleep, insomnia, or other sleep disorder

- Symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning

- Symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance, medication, or general medical condition

Note: The content on Sleepopolis is meant to be informative in nature, but it shouldn’t be taken as medical advice, and it shouldn’t take the place of medical advice and supervision from a trained professional. If you feel you may be suffering from any sleep disorder or medical condition, please see your healthcare provider immediately.

Types and Causes of Hypersomnia

Hypersomnia may be a primary sleep disorder — meaning it occurs without an apparent cause — or secondary, which means that symptoms can be attributed to other disorders, illnesses, or lifestyle choices.

Types of primary hypersomnia include:

- Narcolepsy – Symptoms of narcolepsy include excessive daytime sleepiness and “sleep attacks,” which may cause the sufferer to immediately and uncontrollably fall asleep. The disorder is thought to result from an autoimmune response to a viral infection, and most commonly begins in childhood

- Kleine-Levin syndrome – A rare disorder characterized by periods of excessive daytime sleepiness and increased hours of sleep, followed by unusually high sex drive, hunger, and a heightened feeling of being awake. Kleine-Levin syndrome may result from problems in the temporal lobe of the brain, along with hormonal imbalances (17)

- Idiopathic hypersomnia – Hypersomnia with no diagnosable cause. Sufferers may never feel fully awake despite consistently adequate sleep

Secondary hypersomnia occurs because of another disorder or condition, or as a side effect of certain medications. Because this type of hypersomnia has a specific cause, it may be easier to diagnose and treat. Conditions that may cause hypersomnia include:

- Epilepsy

- Multiple sclerosis

- Obesity

- Heart disease

- Chronic pain

- Head injuries

- Low thyroid function

- Mood disorders, particularly depression (18)

Secondary Hypersomnia And Other Sleep Disorders

A common cause of secondary hypersomnia is other sleep disorders, particularly those that affect breathing and movement and lead to frequent sleep disruptions. These disorders include:

- Sleep Apnea — Sleep apnea is the most common sleep-related cause of secondary hypersomnia (19). The disorder occurs when the upper airway becomes blocked, reducing or stopping the flow of air to the lungs. Sleep apnea may also cause shallow breathing, which can result in a lack of oxygen. Sleep apnea increases the risk of stroke, and may contribute to obesity and heart disease

- Restless leg syndrome, or RSL — RSL causes a strong and irresistible urge to move the legs, particularly while resting. Sufferers typically describe uncomfortable or painful sensations which are only alleviated by movement. Because the disorder usually occurs at night and at bedtime, symptoms can cause daytime sleepiness that interferes with work, school, and family obligations

Diagnosing Hypersomnia

Doctors may suspect hypersomnia if unusual daytime sleepiness persists for three consecutive months, at least three days each week. When doctors suspect hypersomnia, they may conduct sleep tests such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and Multiple Sleep Latency Test, or MSLT. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale assesses daytime sleepiness, while the MSLT measures a patient’s brain waves, eye movements, and muscle activity during a sequence of naps in a sleep study setting.

Once excessive daytime sleepiness is diagnosed, doctors may conduct a complete medical examination to screen for possible causes, along with tests to check for other sleep disorders.

Hypersomnia Treatment

Treatment of hypersomnia depends on the cause and symptoms of the disorder, as well as age and medical condition. The treatment of secondary hypersomnia typically involves addressing the underlying cause, which may be a medical condition, mood disorder, drug side effect, or other sleep disorder. If the condition resolves, the associated symptoms of hypersomnia typically resolve, as well.

Current treatments for primary hypersomnia are limited to medications to treat symptoms of excessive sleepiness, as well as good sleep hygiene and alternative therapies such as guided imagery.

Medication

Primary hypersomnia may be treated with stimulants, some of which are commonly used for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. These medications may help sufferers feel more awake, well-rested, and focused. Antidepressants such as fluoxetine, sertraline, or citalopram are also used to treat the disorder.

Flumazenil, a medication that was FDA-approved to reverse the effects of benzodiazepines, is sometimes used off-label to treat hypersomnia. Because it is an injection, it is often compounded into a cream for use by hypersomnia sufferers. Sodium oxybate may be helpful for treating some of the symptoms of narcolepsy. (20)

Sleep Hygiene

Hypersomnia sufferers may benefit from good sleep hygiene, which includes simple lifestyle changes such as:

- Heading to bed at the same time every night. A regular bedtime trains the body to know when it’s time to sleep

- Using the bed only for sleep and sex

- Removing electronics such as TV’s, smart phones, and computers from the bedroom

- Avoiding caffeine, alcohol, and large meals before bed

- Keeping the bedroom quiet, cool, and dark

- Eliminating noise and disruptions from pets and children

Other hypersomnia therapies may include yoga, hypnosis, and meditation, which can help some hypersomnia sufferers relax, control anxiety, and become aware of subtle symptoms that signal when a sleep attack is likely to happen.

CBT-H (cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia) is a new area of treatment that has shown promise for hypersomnia patients, as well. The pilot study used techniques such as:

- Following regular daytime and nighttime routines

- Managing anxiety and depression linked to hypersomnias

- Improving self-efficacy

The Future of Sleep Disorders Treatment

Recent advances in sleep medicine have led to a greater understanding of many sleep disorders, including insomnia and hypersomnia. In the last few years, diagnostic criteria for both disorders has been updated. Narcolepsy is now known to be a disorder of auto-immune origin. Hyperarousal of the nervous system and neurobiological conditioning are understood to play significant roles in chronic insomnia. CBT-I is proving to be an effective insomnia treatment with long-term positive effects. (21)

Though hypersomnia, insomnia, and other sleep disturbances continue to be common, our understanding of these disorders has improved, and sleep has become a focus of health and wellness. From more targeted medications to prevention, new developments in sleep medicine may soon make getting a good night’s sleep much easier.

References

- Michael Grandner, MD, Age and Sleep Disturbances Among American Men And Women: Data From the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Sleep, March 1, 2012

- S. Saddichha, Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Insomnia. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, June 13, 2011

- MH Bonnet, Hyperarousal and insomnia: state of the science, Sleep Medicine Review, Feb. 14, 2010

- MH Bonnet, Insomnia, Metabolic Rate, and Sleep Restoration, Journal of Internal Medicine, July 2003

- DA Kalmbach, Hyperarousal and Sleep Reactivity in Insomnia, Dovepress, Mar. 2018

- Colleen Carney, PhD., The Relation between Insomnia Symptoms, Mood, and Rumination about Insomnia Symptoms, Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, June 15, 2013

- Jason G. Ellis, PhD. The Natural History of Insomnia: Acute Insomnia and First-onset Depression. Sleep, January 1, 2014

- Eric Nofzinger, MD, Functional Neuroimaging Evidence for Hyperarousal in Insomnia, January 28, 2015, American Journal of Psychiatry

- Wetter DW and Young TB. The Relation Between Cigarette Smoking and Sleep Disturbance. National Center for Biotechnology Information, May 23, 1994

- Colin Espie, PhD., Randomized Clinical Effectiveness Trial of Nurse-Administered Small-Group Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Persistent Insomnia in General Practice, Sleep, May 1, 2007

- J. Harris, A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intensive Sleep Retraining (ISR): A Brief Conditioning Treatment for Chronic Insomnia, Sleep, January 1, 2012

- Mahendra P. Sharma, Behavioral interventions for Insomnia: Theory and Practice, Indian Journal of Psychiatry, Dec. 2012

- Janette D. Lie, Pharmacological Treatment of Insomnia, Pharmacy & Therapeutics, November, 2015

- James K. Wyatt, Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia, Sleep Medicine Reviews, June 2003

- Dauvilliers Y, Buguet A., Hypersomnia, Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, Dec. 2005

- Kirstie N. Anderson, Idiopathic Hypersomnia: A Study of 77 Cases, Sleep, Oct. 1, 2007

- Kleine Levin Syndrome: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. PubMed Central (PMC), Oct. 2013

- Dauvilliers Y, Lopez R, Ohayon M, Bayard S., Hypersomnia and Depressive symptoms: Methodological and Clinical Aspects, BioMed Central, Mar. 21, 2013

- Ronald D. Chervin, Approach to the Patient with Excessive Daytime Sleepiness, Up To Date, Sep. 14, 2017

- Bhattarai J, Sumerall S., Current and Future Treatment Options for Narcolepsy: A Review, Sleep Science, Jan. 2017

- Vincenza Castronovo, Long-term Clinical Effect of Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: a Case Series Study, Sleep Medicine, July 2018