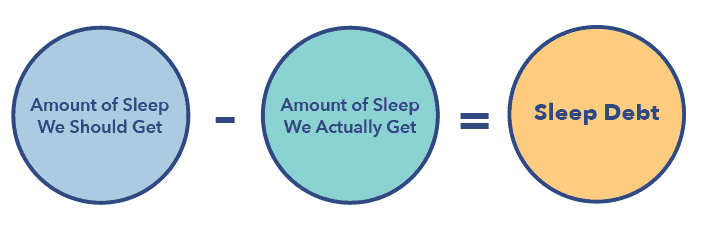

The term sleep debt refers to the difference between the amount of sleep we need and what we’re actually getting. For many of us, it conjures images of a late night studying, time awake with a new baby, or a long flight overseas — in other words, the short-term inconvenience of feeling tired and unable to focus. But let’s take a closer look at the terminology, specifically the word “debt”. It sounds like something we can pay back with a night or two of good rest. But is there any truth to that, or is sleep debt more myth than reality?

Long Story Short

- Sleep debt is the difference between the sleep your body needs (usually 7–9 hours a night for adults) and what you actually get. For example, missing 2 hours of sleep each night for three days adds up to 6 hours of sleep debt.

- Many people believe you can “pay back” sleep debt with a night of good sleep, but in reality, any amount of sleep deprivation can have a lasting impact on your physical and mental health.

- Short-term sleep debt may be manageable, but long-term sleep deprivation can lead to serious health issues, including increased risk for chronic diseases.

- One in five people with significant sleep debt manage to “catch up” on sleep during the weekends, according to research.

- About one in three adults in the U.S. report getting less than 7 hours of sleep per night.

Note: The content on Sleepopolis is meant to be informative in nature, but it shouldn’t be taken as medical advice, and it shouldn’t take the place of medical advice and supervision from a trained professional. If you feel you may be suffering from any sleep disorder or medical condition, please see your healthcare provider immediately. Additionally, restrictions and regulations on supplements may vary by location. If you ever have any questions or concerns about a product you’re using, contact your doctor.

What is Sleep Debt?

Sleep debt is the difference between the amount of sleep you need to feel and function your best and the amount of sleep you actually get. (1) We all have different sleep needs, and consistently getting less sleep than needed can create sleep debt, much like swiping your credit card repeatedly for small purchases can lead to a shocking monthly statement. (2) (3) Let’s say you need 8 hours of sleep to feel refreshed, but for the past 3 nights, you’ve only managed 5 hours of sleep per night. This results in a 3-hour shortfall each night, accumulating to a 9-hour sleep debt over those 3 days.

As sleep debt builds, this accumulation of sleep deprivation can lead to issues like brain fog, constant fatigue, changes in appetite, and mood swings, David Spiegel, MD, founder of Reveri and Associate Chair of Psychiatry at Stanford University, tells Sleepopolis. (4) (5) (6) And while you might think you can fix it all with one or two good nights of sleep, it can be hard to repay an extra 9 hours of sleep. Plus, the effect of sleep debt can linger for days, Spiegel says. (7)

Sleep debt might feel abstract, but it can be measured, and understanding your personal sleep deficit is the first step to better rest. Use our Sleep Debt Calculator to figure out how much sleep debt you’ve accumulated and get tips for getting back on track.

Is Sleep Debt Real?

Sleep debt is real, and researchers have been studying the science of sleep debt and its effects for years. (8) And what they found is significant. Lizzie Benge, MD, a sleep medicine physician and faculty member at Harvard Medical School’s Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, tells Sleepopolis that not getting enough sleep from sleep debt can have short- and long-term consequences on physical and mental health — which we’ll get into later!

You may already know that sleep is a biological necessity. During sleep, your brain goes through much-needed maintenance: rewiring circuits, regulating stress hormones, and activating your body’s “rest and digest” mode. (9) These processes are so important that when you consistently miss out on sleep, the effects are both significant and can be challenging to reverse, Spiegel says.

Causes of Sleep Debt

Pretty much anything that gets between you and your nightly rest can contribute to sleep debt. While some causes might be obvious (like pulling an all-nighter to finish a project), others can sneak up on you. Here are the main culprits behind sleep debt:

- Medical conditions: Sleep disorders like insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and sleep apnea can make it hard to get quality rest. Chronic pain and certain illnesses, including cancer, can also disturb your sleep patterns. (10)

- Lifestyle demands: Your daily schedule can be a major sleep thief. This could be because you do shift work, juggle parental duties with young children, manage a demanding career, or cope with frequent travel across time zones. (11)

- Mental health: Those late-night racing thoughts can be real sleep stealers. Anxiety, depression, stress, and post-traumatic stress disorder can make it difficult to fall asleep or stay asleep throughout the night. (12) (13)

- Daily habits: Some common lifestyle choices can sabotage your sleep without you realizing it. These include nighttime scrolling on your device, caffeine consumption later in the day, and that nightcap. (14)

- Biological changes: Hormonal fluctuations during pregnancy, menopause, or menstrual cycles can throw your sleep schedule off balance. Even certain medications can interfere with your natural sleep patterns. (15) (16)

- Sleep environment: Your bedroom setup matters. A room that’s too hot or too cold, street noise filtering through windows, a snoring partner, or uncomfortable bedding can all chip away at your sleep quality.

Symptoms of Sleep Debt

We all know how we feel when we don’t sleep enough. Sluggish. Forgetful. Irritable. We may have the urge to eat more, and to eat foods high in sugar and carbohydrates. Depending on how sleep-deprived we are, we may also experience: (17)

- Trouble concentrating and making decisions

- Mood changes

- Physical changes, such as being more susceptible to colds, increased appetite, and headaches (18)

- Energy issues, such as feeling tired during the day and relying heavily on caffeine to function

- Sleep pattern changes, such as having trouble falling asleep despite feeling exhausted or finding yourself nodding off during meetings or while watching TV

- Performance problems, such as making more mistakes at work, having slower reaction times, or struggling with coordination

Effects of Sleep Debt

Sleep debt works a lot like a snowball rolling downhill. The longer it builds, the bigger and more overwhelming it can become. Its effects can range from minor nuisances when you don’t get enough sleep for a night or two to serious health issues when the debt accumulates over time.

Short-Term Effects of Sleep Debt

Short-term sleep debt can lead to:

- Impaired concentration: Your brain’s processing speed can take a hit. You might find yourself taking longer to solve simple problems that would usually be a breeze. (19)

- Mood swings: Small frustrations feel like major catastrophes, and your usual easygoing nature might give way to irritability and mood swings. (19)

- Reduced productivity: Tasks that normally take you an hour might stretch to two or three. You might find yourself making more mistakes and spending extra time double-checking your work. (3)

- Clouded judgment: Sleep debt can make you more impulsive and less able to weigh consequences. (3)

- Physical coordination: Your reflexes may slow down, and your hand-eye coordination may suffer. You might also experience microsleep.

The good news is that these short-term effects can be reversed once you get quality sleep.

What’s Microsleep?

Ever catch yourself nodding off for a split second during a meeting? That’s microsleep. It consists of brief, involuntary episodes of unconsciousness that can last from a fraction of a second to a few seconds. While those split-second “nodding off” moments might seem harmless, they can be dangerous if they occur during certain situations like driving, making them a serious warning sign of sleep debt. (20) (21)

Long-Term Effects of Sleep Debt

When sleep debt becomes a chronic issue, lasting weeks, months, or even years, the impact on your health can include:

- Heart health problems: Chronic sleep debt can lead to increased blood pressure and a higher risk of heart issues. (22)

- Memory and brain function: Your brain needs sleep to store and organize memories properly. Being chronically sleep-deprived can cause trouble both in making new memories and hanging onto what you’ve already learned. (23)

- Weight management struggles: Lack of sleep can disrupt hormones that control hunger and fullness, making you more likely to reach for that late-night snack or extra serving. Your metabolism can also slow down, which makes it more difficult to maintain a healthy weight. (24)(25)

- Immune system impact: Chronic sleep debt can make you more susceptible to everything from the common cold and flu to more serious infections. (26)

- Mental health challenges: There’s a link between long-term lack of sleep and increased risk of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. (27) Your emotional resilience suffers when you’re consistently short on sleep.

Myth vs. Reality: Can You Catch Up On Sleep?

The idea of sleeping in on weekends to “catch up” on lost sleep may sound good in theory, but the reality is a bit more complicated. Scientists are still studying exactly how sleep recovery works, but some research shows that how well you catch up depends on how long and severe your sleep debt is. (7)

For short-term sleep loss, the answer is more optimistic. “After short-term sleep loss, getting extra rest for a couple of nights can help you feel better and think more clearly,” Jagdeep Bijwadia, MD, medical director at Complete Sleep, tells Sleepopolis.

Some research suggests there might be benefits to moderate weekend catch-up sleep. In one study, workers who added up to 2 extra hours of sleep on weekends showed healthier cholesterol levels than their peers who didn’t catch up on sleep. (28) But the evidence isn’t conclusive. For example, a small study found that half of the participants who got just 5 hours of sleep during the workweek, followed by unlimited weekend catch-up sleep, and then returned to 5-hour nights still showed biological markers of sleep deprivation on their first day back to restricted sleep. (29)

“Continually pushing the body for arousal and activity without regular adequate rest is dangerous, damages metabolic activity, blood vessels, and brain activity,” Spiegel explains. It can also set you on a path that becomes irreversible over time, he adds.

Recovering from chronic sleep debt can take weeks of consistent, quality sleep, and even then, some effects might linger, Bijwadia notes. While there are ways to recover from sleep (more on that below), your best bet is preventing sleep debt in the first place. (17)

How To Recover From Sleep Debt

You may not be able to “repay” sleep debt like a loan, but you can take steps to recover from it and get your sleep schedule back on track. Here are some strategies that might help: (17)

- Add sleep time gradually: Don’t try to make up for lost sleep all at once. Instead, Bijwadia suggests going to bed 30 to 60 minutes earlier than usual and sticking to it.

- Take naps: A short afternoon nap (keep it under 30 minutes) can help reduce your sleep debt without messing up your nighttime sleep.

- Work on weekend recovery: While you may not be able to fully catch up on sleep on the weekend, allowing yourself an extra hour or two of sleep can help reduce your sleep debt.

- Make sleep quality count: When you’re trying to recover from sleep debt, the quality of your sleep matters as much as the quantity. Create optimal sleeping conditions: a cool, dark, quiet room and a comfortable mattress and pillow.

And if you’re consistently struggling to get enough sleep or feeling excessively tired despite these strategies, Bijwadia recommends talking to a healthcare provider — there might be an underlying sleep disorder that needs attention.

How to Avoid Sleep Debt

The best way to deal with sleep debt is to avoid racking it up in the first place. It begins with understanding your personal sleep needs and creating habits that support quality rest: (30)

- Track your sleep needs: Most adults need 7–9 hours of sleep, but your personal sweet spot might be different. Keeping a sleep diary can help you figure out your ideal amount.

- Create a bedtime schedule: Set specific sleep and wake times that give you enough hours of rest, adjusting in 30-minute increments if you need to change your schedule.

- Design your sleep space: Keep your bedroom cool, dark, and free from distracting electronics.

- Establish evening rituals: Develop a consistent pre-bed routine that helps you wind down, like reading or gentle stretching.

- Adjust your daily habits: Time your caffeine, exercise, and meals earlier in the day to avoid interfering with nighttime sleep.

- Monitor your environment: Invest in comfortable bedding and control noise levels to create optimal sleeping conditions.

- Make sleep non-negotiable: “Sleep is a vital part of your overall health, and it needs to be treated as a priority,” Bijwadia says. That might mean saying no to late-night Netflix binges or setting boundaries.

When to See a Doctor

If you’re consistently struggling with sleep despite your best efforts to catch up and maintain good sleep habits, it might be time to see a healthcare professional. Benge recommends seeking medical help if you’re experiencing persistent daytime fatigue, difficulty concentrating, unexplained weight gain, or mood changes that don’t improve with better sleep habits.

Pay special attention to signs that might indicate a sleep disorder, Bijwadia notes. If you find yourself snoring loudly, waking up gasping for air, experiencing morning headaches, or if someone notices you stop breathing during sleep, these could signal sleep apnea or other serious conditions that require medical evaluation and treatment.

The Last Word From Sleepopolis

Sleep debt can sneak up on anyone, but at Sleepopolis, we’re here to help you stay ahead of it. We bring you expert-backed tips and the latest sleep science to help you take charge of your sleep health. Everyone’s path to better sleep is unique, but the goal is the same: making sleep a priority today for a healthier, more energized tomorrow.

FAQs

Can you recover from sleep debt?

You can recover from sleep debt, especially if it’s just from a few days of poor sleep. But chronic sleep debt may take weeks of consistent, quality sleep to improve, and some effects might be harder to reverse. (7)

How long does sleep debt last?

Sleep debt can last anywhere from a few days to weeks to months, depending on how much sleep you’ve missed.

How is sleep debt calculated?

Sleep debt is calculated by subtracting the amount of sleep you actually get from the amount of sleep your body needs. For example, if you need 8 hours of sleep to be fully refreshed but only get 6 hours, you’ve accumulated 2 hours of sleep debt for that night.

References

- How much sleep is enough? National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-deprivation/how-much-sleep

- Sleep FAQs. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://sleepeducation.org/sleep-faqs/

- What are sleep deprivation and deficiency? National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-deprivation

- Khan MA, Al-Jahdali H. The consequences of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2023;28(2):91-99. doi:10.17712/nsj.2023.2.20220108

- Tomaso CC, Johnson AB, Nelson TD. The effect of sleep deprivation and restriction on mood, emotion, and emotion regulation: three meta-analyses in one. Sleep. 2021;44(6):zsaa289. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsaa289

- Papatriantafyllou E, Efthymiou D, Zoumbaneas E, Popescu CA, Vassilopoulou E. Sleep deprivation: Effects on weight loss and weight loss maintenance. Nutrients. 2022;14(8):1549. Published 2022 Apr 8. doi:10.3390/nu14081549

- Leger D, Richard JB, Collin O, Sauvet F, Faraut B. Napping and weekend catchup sleep do not fully compensate for high rates of sleep debt and short sleep at a population level (in a representative nationwide sample of 12,637 adults). Sleep Med. 2020;74:278-288. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.030

- Åkerstedt T, Ghilotti F, Grotta A, et al. Sleep duration and mortality – Does weekend sleep matter?. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(1):e12712. doi:10.1111/jsr.12712

- Why is sleep important? National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep/why-sleep-important

- Sleep disorders. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/11429-sleep-disorders

- Brito RS, Dias C, Afonso Filho A, Salles C. Prevalence of insomnia in shift workers: a systematic review. Sleep Sci. 2021;14(1):47-54. doi:10.5935/1984-0063.20190150

- Goldberg ZL, Thomas KGF, Lipinska G. Bedtime stress increases sleep latency and impairs next-day prospective memory performance. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:756. Published 2020 Jul 28. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00756

- Oh CM, Kim HY, Na HK, Cho KH, Chu MK. The effect of anxiety and depression on sleep quality of individuals with high risk for insomnia: A population-based study. Front Neurol. 2019;10:849. Published 2019 Aug 13. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00849

- Gardiner C, Weakley J, Burke LM, et al. The effect of caffeine on subsequent sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2023;69:101764. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101764

- Dorsey A, de Lecea L, Jennings KJ. Neurobiological and hormonal mechanisms regulating women’s sleep. Front Neurosci. 2021;14:625397. Published 2021 Jan 14. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.625397

- Sleep problems and menopause: What can I do? National Institute on Aging. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/menopause/sleep-problems-and-menopause-what-can-i-do

- Good News: You Can Make Up for Lost Sleep Over the Weekend (Kind Of). Cleveland Clinic. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/insomnia-can-you-make-up-for-lost-sleep-on-weekends

- Garbarino S, Lanteri P, Bragazzi NL, Magnavita N, Scoditti E. Role of sleep deprivation in immune-related disease risk and outcomes. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):1304. Published 2021 Nov 18. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02825-4

- Thompson KI, Chau M, Lorenzetti MS, Hill LD, Fins AI, Tartar JL. Acute sleep deprivation disrupts emotion, cognition, inflammation, and cortisol in young healthy adults. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:945661. Published 2022 Sep 23. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2022.945661

- NIOSH Training for Nurses on Shift Work and Long Work Hours – Negative impacts on sleep. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/work-hour-training-for-nurses/longhours/mod3/03.html

- How sleep affects your health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-deprivation/health-effects

- About sleep and your health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/sleep-and-heart-health.html

- Cousins JN, Fernández G. The impact of sleep deprivation on declarative memory. Prog Brain Res. 2019;246:27-53. doi:10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.01.007

- Anderson KC, Hasan F, Grammer EE, Kranz S. Endogenous ghrelin levels and perception of hunger: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2023;14(5):1226-1236. doi:10.1016/j.advnut.2023.07.011

- Al-Hussaniy HA, Alburghaif AH, Naji MA. Leptin hormone and its effectiveness in reproduction, metabolism, immunity, diabetes, hopes and ambitions. J Med Life. 2021;14(5):600-605. doi:10.25122/jml-2021-0153

- NIOSH Training for Nurses on Shift Work and Long Work Hours – Sleep and the immune system. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/work-hour-training-for-nurses/longhours/mod2/05.html

- Blackwelder A, Hoskins M, Huber L. Effect of inadequate sleep on frequent mental distress. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E61. Published 2021 Jun 17. doi:10.5888/pcd18.200573

- Jang YS, Park YS, Hurh K, Park EC, Jang SI. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and dyslipidemia among Korean workers [published correction appears in Sci Rep. 2023 Feb 14;13(1):2615. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-29768-6]. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):925. Published 2023 Jan 17. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-28142-w

- Gombert M, Reisdorph N, Morton SJ, Wright KP Jr, Depner CM. Insufficient sleep and weekend recovery sleep: classification by a metabolomics-based machine learning ensemble. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21123. Published 2023 Nov 30. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48208-z

- Healthy sleep habits. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://sleepeducation.org/healthy-sleep/healthy-sleep-habits/